Ian Nairn

Notting Hill Editions, Reissue 2025, 192 pages

Hardback £16.99 | ISBN 9781912559633

Review by Janet Mackinnon

“It is an outrage on posterity to misuse a single yard of land…the outrage has been more than sufficiently perpetrated already.”

George Stapledon, The Land Now and Tomorrow (1935/44)

In 1954, Ian Nairn began a road odyssey from southern England to Scotland that would find expression the following year in his best-known work and the subject of this review: Outrage. A mathematics graduate and RAF pilot during National Service, Nairn subsequently embarked upon a writing and broadcasting career that would focus on Britain’s urban heritage and post-war planning. However, a key inspiration for his first book was the work of George Stapledon, a grassland scientist and ‘pioneer environmentalist’, credited with saving the country from food insecurity – or being ‘starved in to submission’ – by then Minister of Agriculture Colonel Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith at the start of World War II.1,2 Earlier in his professional life, Stapledon had been a founder member of the British Ecological Society and during the post-war period was a strong advocate of the National Parks movement. In today’s scientific parlance he would probably be considered a proponent of agroecology and his vision for the British countryside and rural areas, whilst incorporating aesthetic and spiritual values, was founded on sustainable land management. Significantly, a 2024 ZSL/BES report highlights land use as critical for nature conservation.3 In some important respects, Ian Nairn’s Outrage took its cue – not least in the title – from Stapledon’s writings on the environment and a more ecocritical approach to his book, and concept of ‘Subtopia’, is, arguably, needed to counterbalance the mainly urbanist perspectives on its legacy.

According to Travis Elborough’s very good introduction to the Notting Hill Editions 2025 reissue: “Outrage exploded like a grenade in the shabby genteel world of mid-fifties Britain.” Another comparison might be to one of the ‘helpful bombs’ invoked by John Betjeman in the infamous 1937 poem ‘Slough,’ as both he and Nairn found a platform for their respective views on Britain’s countryside and townscapes at The Architectural Review, which first published Outrage in the form of an extended essay. However, elite and popular concern about inappropriate development of England’s green and pleasant land had been widely articulated since the mid-1920s leading to the creation of CPRE in 1926. Publications such as Clough Williams-Ellis’ England and the Octopus (1928) and J B Priestley’s English Journey (1934) followed with growing criticism of urban sprawl only temporarily slowed (if not halted) by the outbreak of World War II and its immediate aftermath. With his pilot’s eye and understanding of aerial photography, Ian Nairn brought fresh perspectives from this wider hinterland of outrage, and he was just the sort of angry young man to articulate these for a new conservation movement.

The publication of Outrage contributed to the foundation of the Civic Trust in 1957 by Lord Duncan-Sandys, the son-in-law of Winston Church and a former housing minister, who had introduced Green Belt legislation in 1955. Sandys was an establishment insider and pro-European who played a pivotal role in mid-20th century British Conservatism. The Civic Trust movement, involving many local and regional voluntary organisations, was an important feature of built environment conservation in Britain for over 50 years. By contrast, notwithstanding a prolific career as a writer and broadcaster, Ian Nairn largely remained a social outsider until his untimely death in 1983 when he was contemplating a book on London’s countryside. This might have restored something of the vital inspiration for his first published work: a strong feeling that rural and ‘wild’ landscapes must be conserved, and urban areas should, as far as possible, be contained and evolve through good quality spatial planning. His visceral outrage about the shortcomings of development control and unplanned evolution of subtopia in some respects looks forward to the contemporary notion of ‘enshittification’. Originally used to describe our increasingly dystopian online world, the concept also suggests pollution of the countryside by a combination of modern intensive agriculture and urban sprawl.

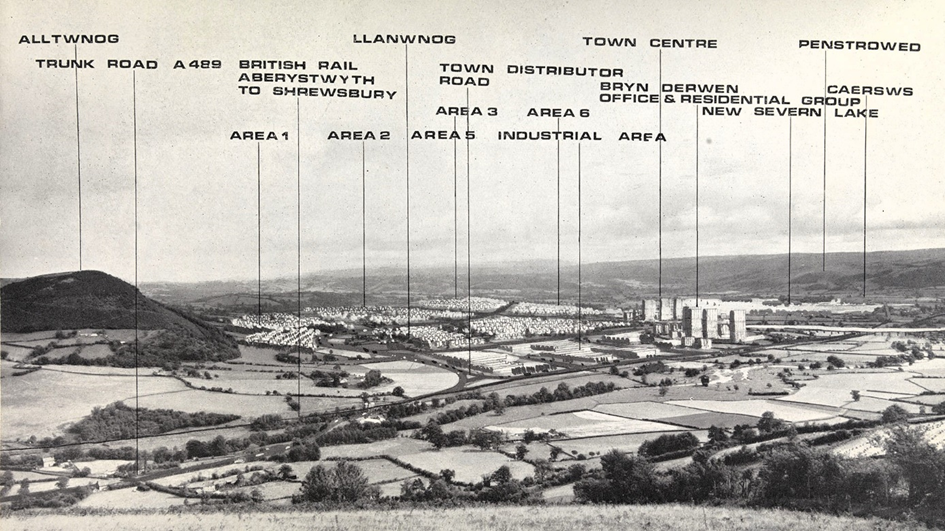

Thus, while Outrage is inevitably a work of its time, in part based upon observation of historic land-use change, its core messages lend themselves to present subtopian predicaments. In a 2022 contribution to Resilience, ECOS interviewee Simon Fairlie shares an extract from Going to Seed: A Counterculture Memoir in which he writes: “The 1950s was arguably the decade that best matched a decent standard of living to a sustainable way of life”.4 While many will challenge this statement, others like me will agree the 1950s was probably the last decade in Britain when more sustainable forms of land use, built environment and regional development could have evolved. By way of example, as Fairlie notes, most of the country then still had a well-connected public transport system but much of this would be closed down from the 1960s onwards, although sections are now being re-instated (at considerable expense). What might be described as the subsequent ongoing battle between sustainability and subtopia is well illustrated in two historic images from my locale. The first shows the (now dismantled) railway line to Llanidloes, a small Mid-Wales town later praised by Ian Nairn for its siting and buildings (at one time including a train station). The second depicts a proposed huge linear conurbation (fortunately not developed) extending from Newtown, Powys to Llanidloes and centred on the village of Caersws, which did retain its rail connection.

Photo: Wikipedia

Photo: Consultants’ photomontage

By way of coincidence, I read much of Outrage – an admirably short book – during the wait for a delayed train to Aberystwyth. Beyond a fleeting acknowledgement of 1950s urban sprawl along parts of the Welsh Coast and Valleys, Nairn does not tackle Wales in this volume, but his inspiration George Stapledon had important connections to the University of Aberystwyth, where he led grassland research, and had supported protected status for parts of the Cambrian Mountains since the mid-1930s.5 However, some of the key issues identified by Nairn on his arrival in the Scottish Highlands increasingly applied to the popular tourist areas of the Welsh coast, hills and mountains. These problems include ‘over-tourism’ in the unabated expansion of holiday parks for caravans and more upmarket lodges. Alongside the emerging visitor economy subtopia, encountered by Outrage in the 1950s English Lake District, Nairn also objected to an increasingly obtrusive network of electricity pylons with a foresight that anticipates current heated controversies around the infrastructure purportedly needed for renewable energy and the, arguably, subtopian dream of Net Zero. In contrast, Nairn makes a strong case for the protection of the “only big area of Great Britain (Highlands) that is still wild…” in a plea that looks forward to contemporary rewilding discourses.

Outrage employs the spatial classification of ‘town’, ‘suburb’, ‘country’ and ‘wild’. While he reserves the latter designation for parts of Scotland only, making comparison with Norway, and focuses extensively on urban categories, Ian Nairn still has much that is still relevant to say about rural England and, indeed, Wales. Moreover, his strong pre-occupation with landscapes reflecting British wartime re-armament and defence, along with the effective militarization of large tracts of countryside unfortunately also speaks to the present era of conflict in Europe and its many negative environmental impacts. Although serving briefly in the air force and holding a pilot’s license, Nairn’s worldview is summed up simply in the words: “Whoever got anywhere by living from war to war.” Instead, his battle is with post-war dark forces assailing Britain’s natural and built heritage facilitated by weakened government regulation, local planning departments and diminished civil society. For the latter, Outrage offers a ‘manifesto’ and call to arms, with an orderly action plan for interventions in decision-making about the environment based on a ‘checklist of malpractices’ in the four spatial contexts listed above.

Although essentially taking the form of a travel notebook detailing subtopian outrages in writing and pictorially along its route, Ian Nairn’s book makes reference to Gulliver’s Travels (discussed in an ECOS journey through ecological fictions) thereby hinting at a more literary and philosophical hinterland. This is briefly described in the ‘anthology’ which concludes Outrage, including references to the works of George Stapledon and well-known mid-20th century archaeologist and natural history writer Jacquetta Hawkes, who became the wife and intellectual collaborator of J B Priestley. Although not mentioned by Nairn, one of Hawkes’ best-known publications, A Land, is now regarded as a classic piece of British nature writing and captured a resurgence of post-war public interest in the natural as well as built environments. Outrage is located very much at the intersection of these and for a short book still packs a great deal of punch. Inevitably Nairn does not quite anticipate the full scale or horrors of contemporary Subtopia – but some of these are covered in Travis Elborough’s introduction to the Notting Hill Editions reissue – including the extent to which accompanying ‘traffication’ has impacted upon Britain’s towns and countryside. As for Nairn’s dreaded ‘Things in Fields’, one need look no further than the multitude of large sheds for intensive agriculture whose increasing ‘enshittification’ of lakes and rivers has created so-called ‘sacrifice zones’ in some rural areas.6 Let me end with two quotes from Outrage but substitute ‘wilder’ for ‘greener’:

“The more complicated our industrial system, and the greater our population, the bigger and greener should be our countryside, the more compact and neater should be our towns…”

“Let us remember then that Nature is not to be denied. There is a nemesis prepared for those who ignore this simple fact…”

References

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Stapledon

2. https://www.environmentandsociety.org/mml/sir-george-stapledon-1882-1960-and-landscape-britain

3. https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/transform-uk-land-use-approach-for-a-sustainable-future

4. https://www.resilience.org/stories/2022-02-14/going-to-seed-excerpt

5. https://www.cambrian-news.co.uk/news/a-long-wait-indeed-for-the-cambrian-mountains-status-603660

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/oct/02/uk-fifth-worst-country-in-europe-for-loss-of-green-space-to-development