With rewilding in danger of becoming all things to all people we argue the need for a unified definition and a set of guiding principles to keep it distinctive and close to its ecological roots. Urgent action is needed to get rewilding back on track as the UK Government gears up to include rewilding in conservation and climate change policy.

Remember the days when rewilding was niche and novel? When 99% of people had never heard of it, even within the conservation sector? Well, those days are long gone. Everyone has heard of rewilding and everyone and their dog is doing it, or so it would seem. From Radio 4’s The Archers to the National Trust, rewilding is definitely on the agenda. Even the PM is talking about it, spurred on no doubt by pillow talk with Carrie and father-son chats with Stanley. HM Treasury is in on the act too, with the recent Dasgupta Review and its short, if slightly odd, section on rewilding. Aside from a surprisingly uncritical view of Oostvaardersplassen, the view that rewilding can be “applied on individual farms” perhaps needs to be questioned as to us, this sounds suspiciously like someone from Team Dasgupta has an over-fondness for ‘Knepp Wildland’. Whilst that particular project may offer some conservation value in terms of improved habitat and increased biodiversity, it has limited connectivity and is still a livestock farm at the end of the day.

Rewilding greenwash

We take issue with the way Dasgupta aligns neoliberal economic policy with the need for a transformative relationship with nature: surely this is just throwing more oil on the fire? But the review does at least say some interesting things about nature-based education and GDP, and the very fact that it mentions rewilding at all demonstrates how far the concept has reached into mainstream politics and policy.

This of course is likely to come at a price, and we have already seen ‘rewilding greenwash’ in the guise of the Government’s ‘Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution’, which contains promises to increase the amount of land protected for nature within the UK to 30% by 2030 along with proposals to create ten new landscape recovery projects equivalent to 30,000 football pitches of wildlife-rich habitat. The fact that the 30% figure only amounts to a 4% increase in new National Parks or AONBs (which are in themselves not natural areas at all but protected cultural landscapes) and 30,000 football pitches equates to as little as 0.07% of England, doesn’t seem to matter next to the spin and hyperbole. In short, rewilding has become a movement, the new saviour, and the latest cause célèbre among the environmentally woke and metropolitan elite.

All things to all people?

Somewhere along the way, rewilding has become all things to all people; at least when discussing conservation and nature protection. Literally any intervention that leads to a slightly wilder outcome, whether it is reinstating hay meadows or managed coastal realignment or reintroducing beaver within enclosures, is being called rewilding these days. This is happening to such an extent that rewilding has become a “plastic term”, meaning that it has been moulded and manipulated to fit almost anything we wish and, in the process, now covers a vast range of both passive and active management interventions (Jørgensen, 2015). These include such things as Pleistocene megafauna replacement, taxon replacement, species reintroductions, retro-breeding and release of captive bred animals, land abandonment and spontaneous rewilding. It is even being used as a label in farming circles for so-called conservation grazing; witness how Knepp is promoted as the UK’s premier lowland “rewilding” project and is the only UK example cited in the Dasgupta Review.

This probably sounds like we’re being over-critical here, but there is clearly room for the Knepp model as part of an integrated approach to landscape management – with nature compatible farming that offers some connectivity, habitat and biodiversity gains alongside core areas for protection. There is, however, a much bigger question about how this all fits together with more conventional farming and human settlements and infrastructure. Do we take a national or global view on issues such as forestry, farming and conservation? And within that, space for wild nature and rewilding?

While we acknowledge the benefits of wider interest in rewilding, everything that moves the landscape a bit to the right on the wilderness continuum isn’t rewilding. This is nicely demonstrated by the on-going debate as to where rewilding sits relative to ecological restoration, wherein some have suggested that rewilding is too fuzzy a term and would be better framed within the established field of ecological restoration. We maintain that rewilding may be a sub-discipline of restoration but, critically, we recognise that not all restoration is rewilding.

At a broad level, rewilding has evolved to encapsulate a range of societal themes including the relationships between humans and nature, deep ecology, ecotourism, bushcraft and rewilding hearts and minds. We would argue that on one level this is undoubtedly a good thing and reflects a long tradition of rewilding philosophy and ethics (see for example Peter Taylor’s 2019 ECOS article ‘Principles of rewilding from the heart’). Protecting, promoting and actively creating space for wild nature is back on the popular agenda, which is heartening, but calling everything “rewilding” could risk diluting the idea to such a point that it loses its original meaning. As Tony Sinclair so eloquently put it: “In the end if a term, either restoration or rewilding, applies to everything, it also means nothing”.

This potentially leads to confusion, woolly thinking and opposition from the more traditional land management and conservation sector. We are (again) sorry if this seems a little negative but there is a point to this, and words and their meanings are important because it is how we communicate ideas. The lack of consistent use is widely recognised as being responsible for the misrepresentation of rewilding in both practice and policy application (Pettorelli et al, 2018). While some researchers highlight rewilding’s multivalence as encouraging diversity, creativity and debate(Deary and Warren, 2017), others suggest that this may actually distract from the ecological aims of its original meaning and thus have a diluting effect (Hodder and Bullock, 2010). Scrutiny of the number of organisations, institutions and landowners with “rewilding” in their title or promoting it as a label for activities best described as restoration or remediation reveals the extent of this issue. Much of what they do cannot be regarded as rewilding if we take the strict ecological definition as safeguarding and restoring a region’s native diversity through large-scale, interconnected networks of reserves, with a focus on strongly interacting keystone species and their trophic relationships (Power et al, 1996).

The ecological foundations of rewilding

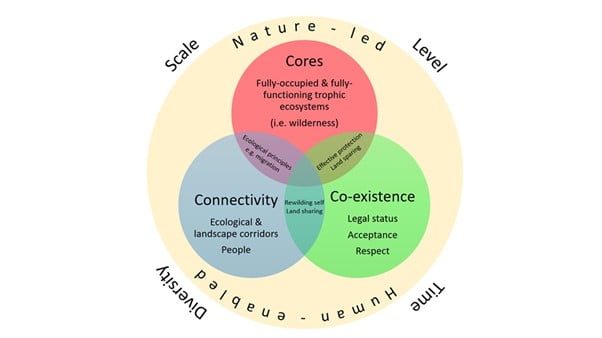

At its heart, the fundamental scientific basis for rewilding revolves around three key features: large core protected areas; ecological connectivity; and keystone species. This is the Soulé and Noss “three C’s” model of cores, corridors and carnivores which has been recently refined with the addition of further C’s including Climate resilience (Carroll and Noss, 2020), Compassion (Beckoff, 2014) and Coexistence (Johns, 2019).

You could argue that the basic Geography of the UK acts against the true application of such a definition and that rewilding has, by necessity, become watered down to a more pragmatic approach of making things a little bit wilder here and there and doing our best to fit this into the existing land use mosaic. Here there is simply not the space (nor indeed the political or economic will) in such a small and crowded island nation. Physical (and political) isolation from the European mainland has huge implications for the 3Cs approach to rewilding. If the model of continental scale conservation is to work here, we need to up the ante on carnivore reintroductions.

Despite noises to the contrary, we are yet to see anything approaching the vision of the Lawton Report, which is itself a watered-down version of the 3Cs model. Yes, some things are better, some things are a little bigger but there is little that is more joined. Overall, we are still at the pre-connected stage in our attempts to re-integrate spaces for nature into our landscapes. We do see some glimmer of hope in the ‘Lawtonesque’ Local Nature Recovery Strategy pilots that are currently underway, but our statutory conservation agencies remain chronically under-funded and under-staffed and are not well placed to respond to the institutional challenges presented by rewilding.

A broken system?

Human-led landscape management in its various guises has been part of our statutory agency DNA from the Countryside Commission and English Nature through to today’s politically hamstrung Natural England. The step-change required to move towards rewilding and a nature-led ‘controlled decontrolling’ approach will require much more than some workshops and a new set of planning documents.

Our protected areas are also in a perilous state. As the 2019 Glover Report notes, “National Parks are currently unable to fulfil their statutory purpose to ‘conserve and enhance the natural beauty, wildlife and cultural heritage’ of their areas. Nor is the situation in AONBs any different.” This is a damning finding, and we agree with Glover that the statutory purposes of our landscapes should be renewed. We urgently need to pick up from the failure of the IUCN Putting Nature on the Map process to move our protected areas beyond their current IUCN category IV/V status in all but a few exceptions. What we need now is a Wild Parks review (or similar) and a reorientation of our protected areas towards something more natural.

The usual category V cultural landscapes argument seems hopelessly out of date given the current (and well documented) state of wildlife loss in the UK (Carver and Fisher, 2018). According to Defra’s own 2017 data there are a staggering 2,809,190 sheep in England’s National Parks alone and 9,120,632 ha of farmed land (around 63% of total area). The 2019 Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU) Report Growing Better: Ten Critical Transitions to Transform Food and Land Use sets out some key statistics for UK agriculture, which uses 70% of total land area, employs 1.5% of the workforce and contributes 0.6% of GDP. Agriculture accounts for 11% of greenhouse gas emissions and is the biggest cause of wildlife loss, with a 67% decline in the abundance of priority species since 1970 and 13% of these now close to extinction. It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that our National Parks are overgrazed and resemble nature deserts rather than ‘jewel in the crown’ examples of natural beauty and wildlife. Our Category V Protected Areas are not in the main worthy of being called National Parks. They are essentially large farms with additional levels of planning control. Surely it is time to rewild our protected areas?

Toward a unified model

Despite the many words written and spoken on the matter, rewilding still needs a more unified definition and set of principles which we can all at least aspire to, if not actually follow word for word. To this end, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Commission on Ecosystem Management (CEM) mandated a Rewilding Task Force (RTF) back in 2017 to research the issue and develop such a definition and set of principles.

We have just reported our findings and published these in an open access paper in Conservation Biology along with some 30 co-authors. This list includes some of the original innovators who coined the term back in the 1990s – Michael Soulé, Reed Noss, Dave Forman, Bill Ripple, Tony Sinclair, and the like, alongside their latter-day contemporaries such as Mark Fisher, Sophie Wynne-Jones, Jens Christian Svenning and Laetitia Navarro. Together we surveyed the early pioneers of rewilding, latter day organisations and over 450 articles on rewilding from the scientific and wider literature, including those from the pages of ECOS. From this we have been able to develop and synthesise the following definition and principles (see Box 1), that were then reviewed, consolidated and tested over the space of two years and several international workshops in North America, Europe, Africa and Asia involving input from over 100 experts, academics and practitioners.

IUCN Definition and Guiding Principles for Rewilding

Rewilding: the process of rebuilding, following major human disturbance, a natural ecosystem by restoring natural processes and the complete or near complete food-web at all trophic levels as a self-sustaining and resilient ecosystem using biota that would have been present had the disturbance not occurred. This will involve a paradigm shift in the relationship between humans and nature. The ultimate goal of rewilding is the restoration of functioning native ecosystems complete with fully occupied trophic levels that are nature-led across a range of landscape scales. Rewilded ecosystems should – where possible – be self-sustaining requiring no or minimum-intervention management (i.e. natura naturans or “nature doing what nature does”), recognising that ecosystems are dynamic and not static.

2. Rewilding employs landscape-scale planning that considers core areas, connectivity and co-existence. At the landscape scale, it is crucial that core areas provide a secure space that accommodates the full array of species that comprise a self-sustaining natural ecosystem. These areas may be either legally designated or under private management. Restoring connectivity between core areas promotes movement/migration across the wider landscape and improves resilience to the impacts of climate change. Rewilding can build on existing core areas such as designated wilderness areas, national parks or privately managed natural areas. Plans for rewilding at the landscape scale should accommodate the need for coexistence between wild species and humans (and livestock) through careful integration of cores and connectivity in functioning ecological networks and zoned systems of compatible low-intensity human land use (e.g. buffers and extensive multiple-use landscapes).

4. Rewilding recognizes that ecosystems are dynamic and constantly changing. Temporal change, both allogenic (external) and autogenic (internal), is a fundamental attribute of ecosystems and the evolutionary processes critical to ecosystem function. Allogenic factors include storms, floods, wildfire and large-scale changes in climate. Equally as important are changes from autogenic processes such as nutrient cycles, energy and genes flows, decomposition, herbivory, pollination, seed dispersal and predation. Conservation planning for rewilding should consider the dynamic nature of ecosystems and be responsive to individual species range shifts, and the Rewilding Principles disaggregation and assembly of genes, species and biotic communities. Rewilding should facilitate the space and connectivity needed for these processes to have free reign, allowing the wider processes of succession, disturbance and biotic interactions to determine ecological trajectories without impediment or constraint. Rewilding programmes must take effective population size into account and employ strategies (e.g. connectivity) that ensure there is sufficient reproduction in every generation.

6. Rewilding requires local engagement and support. Rewilding should be inclusive of all stakeholders and embrace participatory approaches and transparent local consultation in the planning process for any project. Rewilding should encourage public understanding and appreciation of wild nature and should address existing concerns about co-existing with wildlife and natural processes of disturbance. Stakeholder engagement and support can reinforce the use of rewilding as an opportunity to promote education and knowledge exchange about the functioning of ecosystems.

8. Rewilding is adaptive and dependent on monitoring and feedback. Monitoring is essential to provide evidence on short and medium-term results with long- term rewilding goals in mind. This is required to determine whether rewilding trajectories, such as a particular treatment, are working as planned. Participatory monitoring using simple crowd-sourced methods with local volunteers coupled with more detailed scientific monitoring can be used to provide the necessary data and information. Rewilding projects should use these data to identify problems and possible solutions as part of an appropriate adaptive management framework. These need to be adequately resourced such that further interventions can be implemented without loss to project budgets and resources.

10. Rewilding requires a paradigm shift in the co-existence of humans and nature. In alliance with the global conservation and restoration communities, rewilding means transformative change, providing optimism, purpose and motivation for engagement alongside a greater awareness of global ecosystems that are essential for life on the planet. This should lead to a paradigm shift in advocacy and activism for change in political will and help shift ecological baselines towards recovering fully functioning trophic ecosystems, such that society no longer accepts degraded ecosystems and over-exploitation of nature as the baseline for each successive future generation. This change in paradigm will also help to create new sustainable economic opportunities, delivering the best outcomes for nature and people.

1. Rewilding utilizes wildlife to restore trophic interactions. Successful rewilding is nature-led, and relies on accommodating predation, competition and other biotic and abiotic interactions to sustain an ecosystem that self-regulates populations that comprise the biotic system. It is crucial that consideration be given to the role large herbivores and apex predators play in maintaining and enhancing the biodiversity within landscapes, together with the value of keystone species in securing the integrity of the ecosystem, and thus enhancing ecosystem resilience. Where appropriate, interactive keystone species that have roles in maintaining the ecosystem should be reintroduced or depleted populations reinforced to an ecologically effective level.

3. Rewilding focuses on the recovery of ecological processes, interactions and conditions based on reference ecosystems. Rewilding should aim to restore the complete or near-complete food-web of a self-sustaining and resilient ecosystem and specifically the natural patterns and dynamics of abundance and distribution of native species. To do this rewilding should make use of an appropriate ecological reference which can be based on: contemporary near-natural reference areas with relatively complete biota where these still exist; and/or scientific evidence supported by expert indigenous and local knowledge. Rewilding should allow for natural disturbance within an evolutionary relevant range of variability and take environmental change into account. Key native species that have become globally extinct can be replaced by suitable carefully selected wild surrogates where legislation permits, their ecological role is deemed important. The surrogate should, where possible, be phylogenetically close to and have similar ecological and trophic functionality as the extinct species and careful management and monitoring be put in place

5. Rewilding should anticipate the effects of climate change and where possible act as a tool to mitigate impacts. Anthropogenic impacts of climate change are rapid and pervasive creating the need to anticipate the likely impacts on rewilding. Rewilding projects have medium to long-term timescales that inevitably span the predicted scales and magnitudes of global climate change as regards warming trends, ice sheet collapse, sea level rise, storm events, etc. and thus climate change needs to be considered when planning such projects. Rewilding can also be considered as an example of a Nature-based Solutions approach (NbS) with the potential to ameliorate and/or tackle the effects of climate change. This includes mitigating the impacts of climate change on ecosystems and increasing the capture of atmospheric carbon (e.g. through natural regeneration following land abandonment and replacing livestock with wild herbivores) as well as providing connectivity along environmental and climatic gradients to enhance opportunities for species movements.

7. Rewilding is informed by both science and indigenous and local knowledge. Practitioner, researcher and indigenous and local knowledge collaborations can generate benefits, maximising innovation and best management guidance through knowledge exchange, transparency and mutual learning. All these forms of knowledge are important for the success of rewilding projects and can help inform adaptive management frameworks. Local experts can provide detailed knowledge of sites, their histories and processes, all of which can help inform rewilding outcomes. It is important to acknowledge knowledge gaps and be aware of shifting baselines and Rewilding Principles the implications of these for rewilding projects. Projects themselves can form the basis for knowledge generation, data and information of use to further projects.

9. Rewilding recognises the intrinsic value of all species and ecosystems. Whilst there is increasing recognition that natural ecosystems, and the species within them, provide valued goods and services to humans, wild nature has its own intrinsic value that humanity has an ethical responsibility to both respect and protect, emphasising values of compassion and coexistence. Rewilding should primarily be an ecocentric, rather than an anthropocentric, activity. Where management interventions are required, these should be the absolute minimum required and use non-lethal means wherever possible.

This definition and its associated principles are focused primarily on the ecological foundations of rewilding (Principles 1-5), acknowledging the importance of human agency (Principles 6 and 7) while maintaining a scientific and ethical stance (Principles 8 and 9) before finally recognising that we, as a society, urgently need to change our relationship with wild nature to ensure a sustainable future for both humans and wildlife. These have been used to develop the broader principles of the Global Rewilding Alliance (GRA) and their Global Charter for Rewilding the Earth (GCRE). They have also been adopted by the Natural Capital Lab in their broader recognition of the need to integrate rewilding with economics.

As part of the IUCN CEM RTF process, we redrew and modified the 3Cs model to broaden its appeal. This revolves around a new 3Cs: Cores, Connectivity and Co-existence utilising a Venn Diagram to demonstrate the overlaps and meanings within the rewilding concept (Figure 1). While not a perfect model, it does capture somewhat the rich picture that is now rewilding without, it is hoped, losing its essence in the process. Within the outer circle, the model emphasises the inherent difference between ecological restoration, stressing here that rewilding is nature-led and human-enabled. In other words, we give nature the space and the time to determine its own trajectory and outcomes, whereas restoration is a more controlled process wherein natural processes are the tool (i.e. human-led, nature-enabled).

Despite this, concerns have been voiced over the Principles for not placing human interests of culture, economics and livelihoods uppermost in their list of priorities. We would argue that this misses the point of rewilding. By placing people centre stage this downgrades the role of natural processes and self-willed nature in building back better ecosystems. What is clear as we monitor and observe the ongoing trajectory of rewilding in the UK (and perhaps in many a country elsewhere), is that it is in danger of losing its true meaning and, to paraphrase one of the co-authors of the new guiding principles, “it is time to put the wild back into rewilding”.

References

The Economics of Biodiversity https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/final-report-the-economics-of-biodiversity-the-dasgupta-review

Jørgensen D. 2015. Rethinking rewilding. Geoforum 65:482-488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.11.016

Taylor, P “ECOS 40(6): Principles of rewilding – from the heart” ECOS 40(6), 2019, British Association of Nature Conservationists, www.ecos.org.uk/ecos-406-principles-of-rewilding-from-the-heart/.

Tony Sinclair (2017) The Future of Conservation: Lessons From the Past and the Need for Rewilding of Ecosystems. https://youtu.be/hAGYP9-cZ7Q

Pettorelli, N., Barlow, J., Stephens, P.A., Durant, S.M., Connor, B., Schulte to Bühne, H., Sandom, C.J., Wentworth, J. and du Toit, J.T., 2018. Making rewilding fit for policy. Journal of Applied Ecology, 55(3), pp.1114-1125.

Deary H, Warren CR. 2017. Divergent visions of wildness and naturalness in a storied landscape: Practices and discourses of rewilding in Scotland’s wild places. Journal of Rural Studies 54:211-222.

Hodder, K. and Bullock, J., 2010. Nature without nurture. Restoration and history: the search for a usable environmental past, pp.223-235.

Power ME, Tilman D, Estes JA, Menge BA, Bond WJ, Mills LS, Daily G, Castilla JC, Lubchenco J, Paine RT. 1996. Challenges in the quest for keystones: identifying keystone species is difficult—but essential to understanding how loss of species will affect ecosystems. BioScience 46(8):609-620. https://doi.org/10.2307/1312990

Soulé ME, Noss R. 1998. Rewilding and biodiversity: complementary goals for continental conservation. Wild Earth 8(3):18-28.

Carroll C, Noss RF. 2020. Rewilding in the face of climate change. Conservation Biology 0:1-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13531

Bekoff M. 2014. Rewilding Our Hearts: Building Pathways of Compassion and Coexistence. New World Library, Novato, California.

Johns D. 2019. History of rewilding: Ideas and practice. Pages 12-33 in Pettorelli N, Durant S, du Toit J. editors, Rewilding, Cambridge University Press.

Lawton, J.H., Brotherton, P.N.M., Brown, V.K., Elphick, C., Fitter, A.H., Forshaw, J., Haddow, R.W., Hilborne, S., Leafe, R.N., Mace, G.M., Southgate, M.P., Sutherland, W.J., Tew, T.E., Varley, J., & Wynne, G.R. (2010) Making Space for Nature: a review of England’s wildlife sites and ecological network. Report to Defra. http://archive.defra.gov.uk/environment/biodiversity/documents/201009space-for-nature.pdf

Carver, S. and Fisher, M., 2018. Reviewing England’s National Parks: an opportunity for rewilding?. ECOS 39(3). https://www.ecos.org.uk/8984-2/

Farming Statistics, Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Available from defra-stats-foodfarm-landuselivestock-june-results-nationalparks-16jan18, accessed: 09/05/21

FOLU 2019 Growing Better: Ten Critical Transitions to Transform Food and Land Use.

The Global Consultation Report of the Food and Land Use (FOLU) Coalition. London.

Carver, S. et al., 2021. Guiding principles for rewilding. Conservation Biology. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13730

Wilderness Foundation Global. 2020. Global Charter for Rewilding Earth: advancing nature-based solutions to the extinction and climate crises. https://issuu.com/ijwilderness/docs/rewildingcharter_final2

As a non scientist, unqualified passer-by contributor down the long years, I despair. Reading this – twice, I can be a martyr when I put my mind to it – I cannot see any of this prescription matching the possible; the bar is not just high, it’s out of sight. But these days theologians don’t have to believe in God. In a country of nearly 80 million, many more than when I was born, I think one has to face some pragmatic facts that don’t seem to get noticed by ecologists; perhaps they are just for the birds.

Hi Barry, sorry… I’ve only just seen this comment or I’d have replied immediately. You will have to explain a little more as to what it is that makes you despair. May be I can guess? But firstly, you should be aware that the IUCN CEM Definitions and Principles of Rewilding are global, and might just not apply, in full, to the UK. Here, some principles might have to be seen as aspirational… something to aim for. I think we highlight the problems with applying the principles of rewilding here clear enough in this article, but also see Carver (2014) “Making real space for nature: a continuum approach to UK conservation” ECOS 35 (3/4). You should also see ‘rewilding’ as part of a continuum of approaches. True rewilding… aka rewilding-max or what I cheekily refer to as re(al)wilding, might just not be possible across much of our landscapes, or at least not yet. We’re just too small an island; disconnected from the European mainland (ecologically as well as politically), too intensively farmed, and where not farmed, with too many competing vested-interests jostling for control of the land for full rewilding to be possible. What you seem to be referring to – and forgive me if I’m wrong – is rewilding-lite; the Kneppification of rewilding into a version of HNV focused around regenerative farming using fenced livestock as proxies in conservation grazing regimes. All well and good in its place but as I often say, “if its farming, it ain’t rewilding”. Perhaps, at the end of the day, the problem lies with the word and the way it has been hijacked to mean anything that makes things a little wilder or improves biodiversity a bit. Nothing wrong with such projects, in fact they are all to be applauded, but please don’t call them ‘rewilding’. Call them what they are… remediation, restoration, regenerative. Words matter.